Thoreau writes in his journal:

Concord, Mass. Thoreau writes in his journal:

C. [William Ellery Channing] says he saw skater insects to-day. Harris [Thaddeus William Harris] tells me that those gray insects within the little log forts under the bark of the dead white pine, which I found about a week ago, are Rhagium lineatum. Bought a telescope to-day for eight dollars. Best military spyglass with six slides, which shuts up to about the same size, fifteen dollars, and very powerful . . . C. was making a glass for Amherst College.

Cambridge, Mass. Thoreau checks out Etudes sur les glaciers by Louis Agassiz, A history of New-England by Edward Johnson, and The clear sun-shine of the gospel breaking forth upon the Indians in New England by Thomas Shepard from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 290).

Boston, Mass. Thoreau checks out Travels through the Alps of Savoy and other parts of the Pennine chain, with observations on the phenomena of glaciers by James David Forbes from the Boston Society of Natural History (Emerson Society Quarterly, no. 24 (March 1952):25).

Thoreau writes in his journal:

6.30 A.M.—To Hill.

Still, but with some wrack here and there. The river is low, very low for the season. It has been falling ever since the freshet of February 18th. Now, about sunrise, it is nearly filled with the thin, half-cemented ice-crystals of the night . . .

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau also writes to H.G.O. Blake:

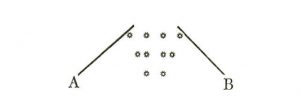

It is high time I sent you a word. I have not heard from Harrisburg since offering to go there, and have not been invited to lecture anywhere else the past winter. So you see I am fast growing rich. This is quite right, for such is my relation to the lecture-goers. I should be surprised and alarmed if there were any great call for me. I confess that I am considerably alarmed even when I hear that an individual wishes to meet me, for my experience teaches me that we shall thus only be made certain of a mutual strangeness, which otherwise we might never have been aware of. I have not yet recovered strength enough for such a walk as you propose, though pretty well again for circumscribed rambles & chamber work. Even now I am probably the greatest walker in Concord—it its disgrace be it said. I remember our walks & talks & sailing in the past, with great satisfaction, and trust that we shall have more of them ere long—have more woodings—up—for even in the spring we must still seek “fuel to maintain our fires.”As you suggest, we would fain value one another for what we are absolutely, rather than relatively. How will this do for a symbol of sympathy

Shall then the maple yield sugar, & not man? Shall the farmer be thus active, & surely have so much sugar to show for it before this very March is gone, while I read the newspaper? While he works in his sugar camp, let me work in mine—for sweetness is in me, & to sugar it shall come; it shall not all go to leaves & wood. I am not a sugar maple man then?

Boil down the sweet sap which the spring causes to flow within you—Stop not at syrup; go on to sugar, though you present the work with but a single crystal—a crystal not made from trees in your yard, but from the new life that stirs in your pores. Cheerfully skim your kettle, & watch it set & crystalize—making a holiday of it, if you will. Heaven will be propitious to you as to him.

Say to the farmer, There is your crop, Here is mine. Mine is sugar to sweeten sugar with. If you will listen to me, I will sweeten your whole load, your whole life.

Then will the callers ask—Where is Blake?—He is in his sugar-camp on the Mt. Mide.—Let the world await him.

Then will the little boys bless you, & the great boys too, for such sugar is the origin of many condiments—Blakeians, in the sops of Worcester, of new form, with their mottos wrapped up in them.

Shall men taste only the sweetness of the maple & the cane, the coming year?

A walk over the crust to Asnybumskit, standing there in its inviting simplicity, is tempting to think of, making a fire on the snow under some rock! The very poverty of outward nature implies an inward wealth in the walker. What a Golconda is he conversant with, thawing his fingers over such a blaze!—but—but—

Have you read the new poem—”The Angel in the House”?—perhaps you will find it good for you.

H.D.T

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

P.M.—To Great Fields . . . Talking with Garfield to-day about his trapping, he said that mink brought three dollars and a quarter, a remarkably high price, and asked if I had seen any . . .

Franklin B. Sanborn writes to Theodore Parker:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

P.M.—To Walden in rain.

A May storm, yesterday and to-day; rather cold. The fields are green now, and the cows find good feed. The female Populus grandidentata, whose long catkins are now growing old, is now leafing out. The flowerless (male?) ones show half-unfolded silvery leaves. Both these and the aspens are quite green (the bark) in the rain . . .

Thoreau writes in his journal:

At Corner Spring, stood listening to a catbird, sounding a good way off . . . Heard a stake-driver in Hubbard’s meadow from Corner road . . .

- First

- Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- Next

- Last