Thoreau writes in his journal:

When I return, about 5 P.M., the shad-flies swarm over the river in considerable numbers, but there are very few at sundown . . . (Journal, 12:201).

Thoreau writes in his journal:

With a north-west wind, it is difficult to sail from the willow-row to Hubbard’s Bath, yet I can sail more westerly from the island point to Fair Haven Bay to the bath-place above: and though I could not do the first to-day, I did sail all the way from Rice’s Bar to half a mile above Sherman’s Bridge by all the windings of the river . . .

On our way up, we ate our dinner at Rice’s shore . . .

A painted turtle laying, at 5 P.M. . . .

At 9 P. M., 54º, and no toads nor peepers heard.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

She [Mrs. Hamilton] said the wild [crab?] apple grew about her premises. Her husband 1st saw it on a ridge by the lake shore. They had dug up several & set them out, but all died. (The settlers also set out the wild plum & thimble berry &c.). So I went & searched in that very unlikely place, but could find nothing like it, though Mrs. Hamilton said there was on ether 3 feet higher than the lake. But I brought home a thorn in bloom instead & asked if that was it. She then gave me more particular directions & I searched again faithfully. & this time I brought home an Amelanchier as the nearest of kin, doubting if the apple had ever been seen there. But she knew both these plants. Her husband had first discovered it by the fruit. But she had not seen it in bloom here. Then called on Fitch & talked about it. He said it was found—the same they had in Vermont (?) & directed me to a Mr. [Jonathan T.] Grimes as one who had found it. He was gone to catch the horses to send his boy 6 miles for a doctor on account of the sick child. Evidently a [?] and enquiring man. The boy showed me some of the trees he had set out this spring. But they had all died, having a long tap root & being taken up too late. But then I was convinced by the sight of the just expanding though withered flower bud to analyze. Finally stayed & went in search of it with the father in his pasture, where I found it first myself, quite a cluster of them.

See a great flight of large ephemera this a.m. on Lake Harriet shore & this evening on Lake Calhoun.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau also writes to Ralph Waldo Emerson in New York:

I see so many “carvels licht, fast tending throw the sea” to your El Dorado, that I am in haste to plant my flag in season on that distant beach, in the name of God and King Henry. There seems to be no occasion why I who have so little to say to you here at home should take pains to send you any of my silence in a letter—Yet since no correspondence can hope to rise above the level of those homely speechless hours, as no spring ever bursts above the level of the still mountain tarn whence it issued — I will not delay to send a venture. As if I were to send you a piece of the house-sill—or a loose casement rather. Do not neighbors sometimes halloo with good will across a field, who yet never chat over a fence?

The sun has just burst through the fog, and I hear blue-birds, song-sparrows, larks, and robins down in the meadow. The other day I walked in the woods, but found myself rather denaturalized by late habits. Yet it is the same nature that [Robert] Burns and [William] Wordsworth loved the same life that [William] Shakspeare and [John] Milton lived. The wind still roars in the wood, as if nothing had happened out of the course of nature. The sound of the waterfall is not interrupted more than if a feather had fallen.

Nature is not ruffled by the rudest blast—The hurricane only snaps a few twigs in some nook of the forest. The snow attains its average depth each winter, and the chic-adee lisps the same notes. The old laws prevail in spite of pestilence and famine. No genius or virtue so rare & revolutionary appears in town or village, that the pine ceases to exude resin in the wood, or beast or bird lays aside its habits.

How plain that death is only the phenomenon of the individual or class. Nature does not recognize it, she finds her own again under new forms without loss. Yet death is beautiful when seen to be a law, and not an accident—It is as common as life. Men die in Tartary, in Ethiopia—in England—in Wisconsin. And after all what portion of this is so serene and living nature can be said to be alive? Do this year’s grasses and foliage outnumber all the past.

Every blade in the field—every leaf in the forest—lays down its life in its season as beautifully as it was taken up. It is the pastime of a full quarter of the year. Dead trees—sere leaves—dried grass and herbs—are not these a good part of our life? And what is that pride of our autumnal scenery but the hectic flush—the sallow and cadaverous countenance of vegetation—its painted throes—with the November air for canvas—

When we look over the fields are we not saddened because the particular flowers or grasses will wither—for the law of their death is the law of new life Will not the land be in good heart because the crops die down from year to year? The herbage cheerfully consents to bloom, and wither, and give place to a new.

So it is with the human plant. We are partial and selfish when we lament the death of the individual, unless our plaint be a paean to the departed soul, and a sigh as the wind sighs over the fields, which no shrub interprets into its private grief.

One might as well go into mourning for every sere leaf—but the more innocent and wiser soul will snuff a fragrance in the gales of autumn, and congratulate Nature upon her health.

After I have imagined thus much will not the Gods feel under obligation to make me realize something as good.

I have just read some good verse by the old Scotch poet John Bellenden—

May nocht be wrocht to our utilitie,

Bot flammis keen & bitter violence;

The more distress, the more intelligence.

Quhay sailis lang in hie prosperitie,

Ar sone oureset be stormis without defence.”

Henry D. Thoreau

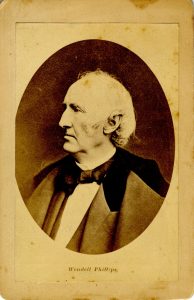

Thoreau attends Wendell Phillips’ Concord Lyceum lecture (The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, 163-166). See entries 12 and 28 March.

Ralph Waldo Emerson to Thoreau:

My dear Sir,I leave town tomorrow & must beg you, if any question arises between Mr [Charles] Bartlett & me, in regard to boundary lines, to act as my attorney, & I will be bound by any agreement you shall make. Will you also, if you have opportunity, warn Mr Bartlett, on my part, against burning his woodlot, without having there present a sufficient number of hands to prevent the fire from spreading into my wood,—which, I think, will be greatly endangered, unless much care is used.

Show him too, if you can, where his cutting & his post-holes trench on our line, by plan and, so doing, oblige as ever,

Yours faithfully,

R. W. Emerson

Thoreau writes in his journal:

That dull-gray-barked willow shows the silvery down of its forthcoming catkins. I believe that I saw blackbirds yesterday. The ice in the pond is soft on the surface, but it is still more than a foot thick. Is that slender green weed which I draw up on my sounding-stone where it is forty feet deep and upward Nitella gracrilis (allied to Chara), described in London?

The woods I walked in in my youth are cut off. Is it not time that I ceased to sing? My groves are invaded. Water that has been so long detained on the hills and uplands by frost is now rapidly finding its level in the ocean. All lakes without outlet are oceans, larger or smaller.

Thoreau writes to George William Curtis:

Together with the ms of my Cape Cod adventures Mr [George Palmer] Putnam sends me only the first 70 or 80 (out of 200) pages of the “Canada,” all which having been printed is of course of no use to me. He states that “the remainder of the mss. seems to have been lost at the printers’.” You will not be surprised if I wish to know if it actually is lost, and if reasonable pains have been taken to recover it. Supposing that Mr. P. may not have had an opportunity to consult you respecting its whereabouts—or have thought it of importance enough to inquire after particularly—I write again to you to whom I entrusted it to assure you that it is of more value to me than may appear.

With your leave I will improve this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of another cheque from Mr. Putnam.

I trust that if we ever have any intercourse hereafter it may be something more cheering than this curt business kind.

Yrs,

Henry D. Thoreau

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Shall the earth be regarded as a graveyard, a necropolis, merely, and not also as a granary filled with the seeds of life? Is not its fertility increased by this decay? A fertile compost, not exhausted sand . . .

P.M.—To Cliffs . . .

Muskrats are driven out of their holes. Heard one’s loud plash behind Hubbard’s . . .

- First

- Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- Next

- Last