Henry D. Thoreau enters Harvard College (Studies in the American Renaissance 1989, 180note).

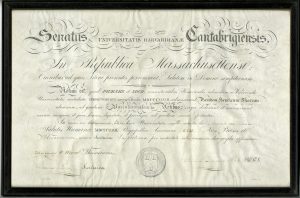

Thoreau graduates from Harvard University.

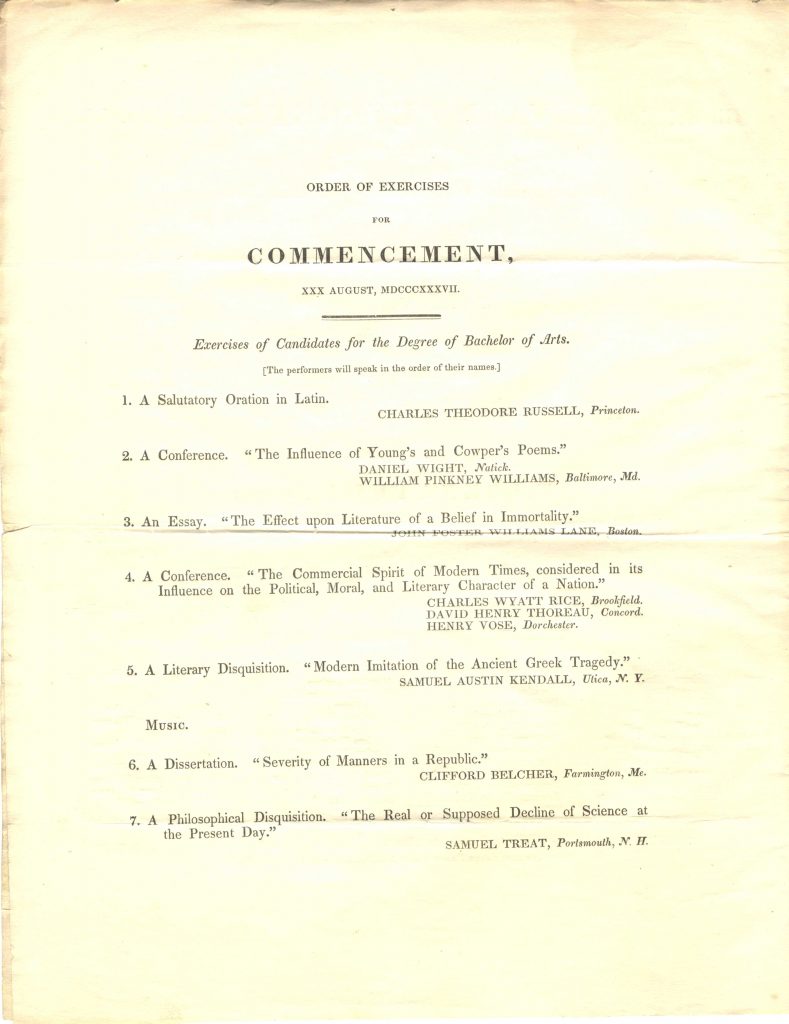

Thoreau participates as one of the speakers of a conference on “The Commercial Spirit of Modern Times, Considered in its influence on the Political, Moral, and Literary Character of a Nation”:

Indeed, could one examine this beehive of ours from an observatory among the stars, he would perceive an unwonted degree of bustle in these later ages. There would be hammering and chipping, baking and brewing, in one quarter; buying and selling, money-changing and speech-making, in another. What impression would he receive form so general and impartial a survey? Would it appear to him that mankind used this world as not abusing it? Doubtless he would first be struck with the profuse beauty of our orb; he would never tire of admiring its varied zones and seasons, with their changes of livery. He could not but notice that restless animal for whose sake it was contrived, but where he found one to admire with him his fair dwelling place, the ninety and nine would be scraping together a little of the gilded dust upon its surface.

In considering the influence of the commercial spirit on the moral character of a nation, we have only to look at its ruling principle. We are to look chiefly for its origin, and the power that still cherishes and sustains it, in a blind and unmanly love of wealth. And it is seriously asked, whether the prevalence of such a spirit can be prejudicial to a community? Wherever it exists it is too sure to become the ruling spirit, and as a natural consequence, it infuses into all our thoughts and affections a degree of its own selfishness; we become selfish in our patriotism, selfish in our domestic relations, selfish in our religion.

Let men, true to their natures, cultivate the moral affections, lead manly and independent lives; let them make riches the means and not the end of existence, and we shall hear no more of the commercial spirit. The sea will not stagnate, the earth will be as green as ever, and the air as pure. This curious world which we inhabit is more wonderful than it is convenient, more beautiful than it is useful—it is more to be admired and enjoyed then, than used. The order of things should be somewhat reversed,—the seventh should be man’s day of toil, wherein to earn his living by the sweat of his brow, and the other six his sabbath of the affections and the soul, in which to range this wide-spread garden, and drink in the soft influences and sublime revelations of Nature.

But the veriest slave of avarice, the most devoted and selfish worshipper of Mammon, is toiling and calculating to some other purpose than the mere acquisition of the good things of this world; he is preparing, gradually and unconsciously it may be, to lead a more intellectual and spiritual life. Man cannot if he will, however degraded or sensual his existence, escape Truth. She makes herself to be heard above the din and bustle of commerce, by the merchant at his desk, or the miser counting his gains, as well as in the retirement of the study, by her humble and patient follower.

Our subject has its bright as well as its dark side. The spirit we are considering is not altogether and without exception bad. We rejoice in it as one more indication of the entire and universal freedom which characterizes the age in which we live—as an indication that the human race is making one more advance in that infinite series of progressions which awaits it. We rejoice that the history of our epoch will not be a barren chapter in the annals of the world,—that the progress which it shall record bids fair to be general and decided. We glory in those very excesses which are a source of anxiety to the wise and good, as an evidence that man will not always be the slave of matter, but erelong, casting off those earth-born desires which identify him with the brute, shall pass the days of his sojourn in this his nether paradise as becomes the Lord of Creation.

“Hard times came to the court in 1837. They were not the new president’s fault, but Van Buren inherited the blame for them nevertheless. People wanted a scapegoat, perhaps, and in Van Buren they soon found one. State Street, the Boston financial section, was hard hit.

Newly graduated from Harvard, Thoreau looked for a job and started a journal. The first item still preserved is short. “ ‘What are you doing now?’ he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry to-day.” Thoreau was already looking for solitude and the opportunity to live his own life. The panic of 1837 find no place in his journal. Thoreau camped by Flint’s Pond for some weeks with his Harvard friend Sterns Wheeler, thus anticipating the Walden experiment.”

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Ralph Waldo Emerson writes to his brother William:

Thoreau surveys the West Burying Grounds for the Town of Concord, requested by John Shepard Keyes (A Catalog of Thoreau’s Surveys in the Concord Free Public Library, 6).

Concord, Mass. Thoreau writes in his journal:

New York, N.Y. The Literary World publishes “An Ascent of Mount Saddleback,” an article by Evert Augustus Duyckinck that references A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

River one or two feet higher than in July. A very little wind from the south or southwest, but the water quite smooth at first . . . Bathed at Hubbard’s Bend . . .

The Solidago odora grows abundantly behind the Minott house in Lincoln. I collected a large bundle of it . . .

Set sail homeward about an hour before sundown. The breeze blows me glibly across Fair Haven, the last dying gale of the day. No wonder men love to be sailors, to be blown about the world sitting at the helm, to shave the capes and see the islands disappear under their sterns,—gubernators to a piece of wood . . .

Thoreau writes in his journal:

P.M.—To Conantum via Clamshell Hill and meadows . . .

I go along through J. Hosmer’s meadow near the river, it is so dry. I see places where the meadow has been denuded of its surface within a few years . . .

Thoreau writes in his journal:

say there has not been such a year as this for more than half a century,—for winter cold, summer heat, and rain.

P.M.—To Vaccinium Oxycoccus Swamp.

Fair weather, clear and rather cool.

Pratt shows me at his shop a bottle filled with alcohol and camphor. The alcohol is clear and the camphor beautifully crystallized at the bottom for nearly an inch in depth, in the form of small feathers, like a boar frost. He has read that this is as good a barometer as any . . .

- First

- Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

- 238

- 239

- 240

- 241

- 242

- 243

- 244

- 245

- 246

- 247

- 248

- 249

- 250

- 251

- 252

- 253

- 254

- 255

- 256

- 257

- 258

- 259

- 260

- 261

- 262

- 263

- 264

- 265

- 266

- 267

- 268

- 269

- 270

- 271

- 272

- 273

- 274

- 275

- 276

- 277

- 278

- 279

- 280

- 281

- 282

- 283

- 284

- 285

- 286

- 287

- 288

- 289

- 290

- 291

- 292

- 293

- 294

- 295

- 296

- 297

- 298

- 299

- 300

- 301

- 302

- 303

- 304

- 305

- 306

- 307

- 308

- 309

- 310

- 311

- 312

- 313

- 314

- 315

- 316

- 317

- 318

- 319

- 320

- 321

- 322

- 323

- 324

- 325

- 326

- 327

- 328

- 329

- 330

- 331

- 332

- 333

- 334

- 335

- 336

- 337

- 338

- 339

- 340

- 341

- 342

- 343

- 344

- 345

- 346

- 347

- 348

- 349

- 350

- 351

- 352

- 353

- 354

- 355

- 356

- 357

- 358

- 359

- 360

- 361

- 362

- 363

- 364

- 365

- 366

- 367

- 368

- 369

- 370

- 371

- 372

- 373

- 374

- 375

- 376

- 377

- 378

- 379

- 380

- 381

- 382

- 383

- 384

- 385

- 386

- 387

- 388

- 389

- 390

- 391

- 392

- 393

- 394

- 395

- 396

- 397

- 398

- 399

- 400

- 401

- 402

- 403

- 404

- 405

- 406

- 407

- 408

- 409

- 410

- 411

- 412

- 413

- 414

- 415

- 416

- 417

- 418

- 419

- 420

- 421

- 422

- 423

- 424

- 425

- 426

- 427

- 428

- 429

- 430

- 431

- 432

- 433

- 434

- 435

- 436

- 437

- 438

- 439

- 440

- 441

- 442

- 443

- 444

- 445

- 446

- 447

- 448

- 449

- 450

- 451

- 452

- 453

- 454

- 455

- 456

- 457

- 458

- 459

- 460

- 461

- 462

- 463

- 464

- 465

- 466

- 467

- 468

- 469

- 470

- 471

- 472

- 473

- 474

- 475

- 476

- 477

- 478

- 479

- Next

- Last